2022/01/22

Hinenosho: Landscape of an old Japanese village

Villages depicted in Tabihikitsuke and two paintings

Landscape of Hinenosho, a manor in medieval Japan

Whenever you come to Izumisano city, “Hinenosho” or old Japanese village welcomes you. It is designated as a Japan Heritage Site. I will introduce you to Hinenosho.

While Izumisano City is now home to Kansai International Airport, a gateway to Japan, the land was a shoen (private manor) called Hinenosho about 800 years ago.

Hinenosho was controlled by the Kujo Family, which was one of Five Sekke (families of upper-class nobles who had ministerial positions as Sessho or Kanpaku, namely the Konoe, Kujo, Takatsukasa, Nijo and Ichijo Families), and covered the whole area of the present-day city. The shoen is depicted in the Masamoto-ko Tabihikitsuke, a diary written by Kujo Masamoto in the early 16th century, and its world is still alive in the form of the rural landscape of the Ogi area, fascinating visitors. The landscape has been maintained as it has evolved along with the progress in the lives of the local people. How was this attractive and nostalgic landscape created? An answer to that question is implied in the two paintings drawn for the development of the Hineno area in the Kamakura Period (1185-1333).

Around 800 years ago, the area of present-day Izumisano City was a territory of the Kujo Family, who were highly ranked nobles. The territory was the shoen (a manor in medieval Japan) called Hinenosho, and two paintings of the shoen and a diary written by Kujo Masamoto, “Tabihikitsuke,” have been conserved. The paintings depict green landscapes, ponds and a watercourse for the irrigation of farms and paddy fields, as well as shrines and temples, while the diary vividly describes the life and people in villages 500 years ago. The landscape that constituted the shoen area has been passed down from the medieval era to present day, and it allows us to enjoy the attractive landscapes of the rural villages presented in the paintings and diary.

Hinenosho was established in 1234. The biggest challenge to its management was the development of vast undeveloped land. The Kujo Family started a land survey of Hinenosho in 1309 and created two paintings during the survey. The watercourse, ponds, shrines and temples in the villages are depicted in the paintings in great detail and surprisingly match the present-day ones.

The main project during development was the construction of the Yukawa Watercourse. It was designed to convey water between Hine Jinja Shrine and Jigen-in Temple and through farms on terraced slopes and to reach Junitaniike Pond over a total length of approximately 2.75 kilometers with a height difference of only about 3 meters. You can get a sense for the painstaking efforts of the village people from the large-scale elaborate civil engineering work.

The ponds created in those days still provide water to farms and paddy fields to grow crops for people. Hinenosho made progress through this large-scale development and grew into an important shoen that developed on its own among the approximately 30 shoen possessed by the Kujo Family in Japan.

Diary of a court noble – Masamoto-ko Tabihikitsuke

In the Warring States Period, the management of shoen began to be threatened by samurai. Around that time, Kujo Masamoto, the lord of Hinenosho, stayed in Chofukuji Temple in the then Ogi area of Iriyamada Village for four years (from 1501).

He wrote a diary to record his life and what happened during those four years.

With plum blossoms in bloom and the green of pine trees deepening, the blessings of a spring day are everywhere thanks to Tenman Tenjin.

During his stay, Masamoto organized renga (linked verse) and other sessions as was commonly done by court nobles. This waka poem, which holds in high regard the spring scenery of the shoen, shows that Tenjin worship was widespread at that time. A small tenmangu shrine stands on the grounds of Sofukuji Temple.

When the villagers in Ogi experienced droughts, they held a ritual to pray for rain at Takimiya Shrine (Hibashiri Jinja Shrine). Noh performances were offered in the ritual, and Masamoto praised them, mentioning that their form and verbal expression were comparable to those of Noh in Kyoto. If it still did not rain after the prayers for rain at Hibashiri Jinja Shrine, the ritual was also held at Inunakisan Shipporyuji Temple. This ritual event is still organized under the name of hotaki in the shrine.

Since ancient times, Shipporyuji Temple has been enshrined as a sacred place for the Shugendo sect of Buddhism on Mt. Inunaki.

The name of the mountain (which means dog barking) derives from the legend of a loyal dog that saved its master’s life from a giant snake. There is also a hot spring area at the mountain, which is rare in Osaka Prefecture.

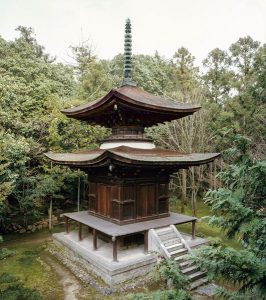

The gestures of the dancers were also not inferior to those of professional performers in Kyoto. A regular festival was held in Oiseki Daimyojin (Hine Jinja Shrine) on April 2 every year. According to his diary, Masamoto was also impressed by the performing arts presented during the festival. Jigen-in Temple is located near the shrine and is across from the Yukawa Watercourse. The two-story pagoda in the temple is one of the three famous two-story pagodas in Japan, and its elegant features have not changed for over 750 years. Masamoto sometimes stayed at Jigen-in Temple.

When the area was attacked by outside forces, the fire bell of Enmanji Temple in Ogi, which is now used as a community gathering place, was rung to inform the whole village. By tracing the history through archives, you can find the footprints of the people who lived in the shoen. The buildings and remains that remain from those days have been conserved, providing us with an image of the medieval era. Thus, Hinenosho is one of the rare shoen in Japan that show us the rule and lives of people and the situations of worship and development at that time in a concrete manner and allow us to experience the conditions of medieval villages.

By Masa Tamura

+81-70-3891-5430

+81-70-3891-5430 contact

contact language change

language change